Introduction: Nietzsche in the Western Canon

Authoritative opening situating Friedrich Nietzsche’s core ideas and their relevance to scholarship and knowledge automation, with timeline, assessments, and SEO guidance.

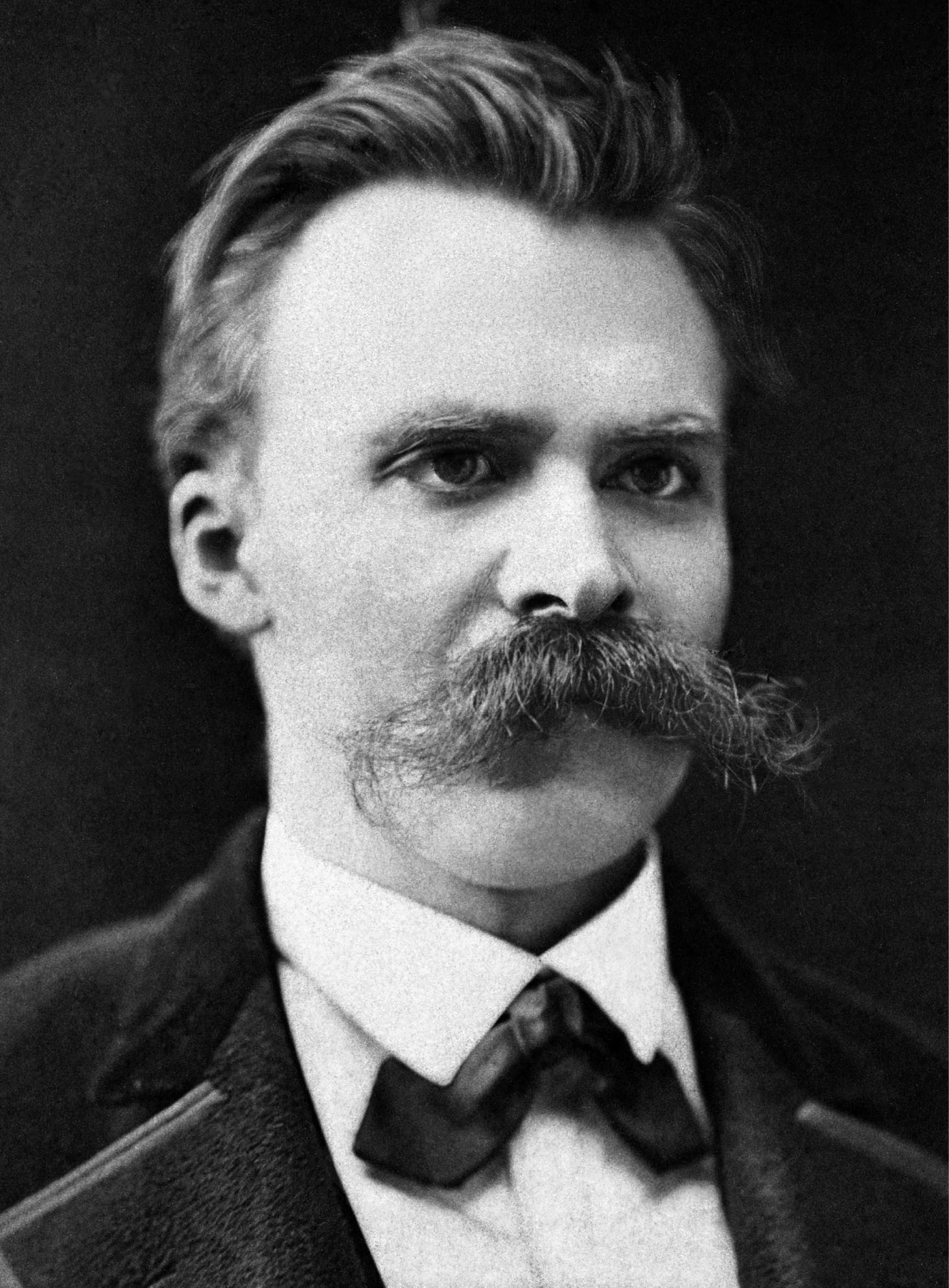

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), the German philosopher and classical philologist at the University of Basel, stands at the center of the Western canon. Through the interlocking ideas of the Übermensch, eternal recurrence, and nihilism, he reframed modern thought about value, agency, and meaning. Born in Röcken and writing in German across philology, philosophy, and cultural criticism, Nietzsche diagnosed the death of God as a cultural fact and challenged scholars to confront its consequences for knowledge, morality, and culture.

These concepts cohere as a single project: nihilism names the historical erosion of inherited absolutes; eternal recurrence operates as an existential stress test for life-affirmation; and the Übermensch designates the creative task of revaluation and self-overcoming. This profile advances the thesis that Nietzsche’s account of value formation provides a toolkit for contemporary research practice and knowledge automation—clarifying provenance, resisting brittle taxonomies, and guiding decision-makers who design classification, retrieval, and governance systems. A brief chronology situates his output; concise scholarly appraisals map reception; and an interdisciplinary vignette links genealogy to data lineage and critical theory. Subsequent sections trace biography, core concepts, methods (genealogy, perspectivism), reception and controversies, and applied frameworks for scholars, knowledge managers, and technology leaders.

Nietzsche: Selected Works Timeline

| Year | Work | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1872 | The Birth of Tragedy | Art against rationalism; Apollonian/Dionysian polarity. |

| 1883–1885 | Thus Spoke Zarathustra | Introduces Übermensch; dramatizes eternal recurrence; critique of herd morality. |

| 1887 | On the Genealogy of Morality | Method of genealogy; origins of values; ressentiment. |

| 1888 | Twilight of the Idols; The Antichrist; Ecce Homo | Late polemics; compressed statements of revaluation. |

Avoid presentism and caricature: do not reduce Nietzsche to later political appropriations or pop-cultural tropes; situate claims within his 1872–1888 corpus and Basel philological background.

Example strong lead sentence: Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), German philosopher and former Basel philologist, forged a method and vocabulary that still organize debates about value in the modern West.

Scholarly Assessments and Interdisciplinary Presence

- Walter Kaufmann: Recast Nietzsche as a rigorous moral psychologist and diagnostician of modernity rather than an irrationalist or proto-fascist.

- Michel Foucault: Credited Nietzsche’s genealogy as the decisive method for analyzing power/knowledge formations.

- Bernard Williams: Read Nietzsche as a central resource for challenging the assumptions of modern moral theory.

- Interdisciplinary example: Nietzschean genealogy informs critical theory and, by analogy, data lineage frameworks in knowledge management (tracing provenance, transformations, and value-claims).

Roadmap of Sections

- Biographical chronology and context (Basel appointment; productivity; collapse).

- Core concepts: Übermensch, eternal recurrence, nihilism—conceptual interrelations.

- Methods: genealogy and perspectivism for research practice.

- Reception and debates: modern scholarship and controversies.

- Interdisciplinary influence: existentialism, critical theory, cognitive frameworks.

- Applications: research workflows, classification, governance, and knowledge automation.

- Annotated bibliography and extended timeline.

SEO Meta Examples

- Title tag: Friedrich Nietzsche in the Western Canon: Übermensch, Eternal Recurrence, Nihilism

- Meta description: Authoritative introduction to Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900): Basel philologist-turned-philosopher whose Übermensch, eternal recurrence, and nihilism shape scholarship and knowledge systems today.

Professional Background and Career Path

A concise, source-grounded chronology of Nietzsche’s academic formation in classical philology, his rapid rise at the University of Basel in 1869, and the health- and network-driven transition to an independent philosophical career after his 1879 resignation.

Friedrich Nietzsche career milestones began with rigorous classical training at Schulpforta (1858–1864). He entered the University of Bonn (1864–1865) to study theology and classical philology, soon committing to philology under Friedrich Ritschl. Following Ritschl to Leipzig (1865–1869), he refined his philological method and encountered Schopenhauer, a bridge from textual scholarship to philosophical inquiry. Military service (1867–1868) briefly interrupted his studies. In March 1869, Leipzig awarded him an honorary doctorate based on published work rather than a formal dissertation. The Nietzsche University of Basel appointed him in April 1869, at age 24, as Extraordinary Professor of Classical Philology—an exceptional early appointment that anchored the Friedrich Nietzsche career in academia.

Promoted to Ordinary Professor in 1870 (with tenure and a salary increase typical of the rank), Nietzsche taught at Basel through the 1870s, interspersed with leaves for severe migraines, eye trouble, and illnesses contracted while serving as a medical orderly in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871). Networks shaped key turns: Ritschl’s endorsement secured Basel; his friendship with Richard Wagner energized early Basel years and informed The Birth of Tragedy (1872), while their later estrangement aligned with a shift toward independent philosophy marked by Human, All Too Human (1878). Mounting health problems led to his resignation from the Basel chair in 1879; the university granted a modest pension, enabling a decade of itinerant intellectual work (Sils-Maria, Genoa, Nice, Turin), during which he fully transitioned from philology to philosophy and produced his most influential writings.

- Micro-example timeline:

- 1858–1864: Schulpforta — classical languages and philological training.

- 1864–1865: University of Bonn — theology and philology; pupil of Friedrich Ritschl.

- 1865–1869: University of Leipzig — classical philology; military service interlude (1867–1868).

- Mar 1869: Honorary doctorate, University of Leipzig — awarded on publications.

- Apr 1869–1879: University of Basel — Extraordinary/then Ordinary Professor (promoted 1870); resigned 1879 to write full-time.

Academic timeline and career transitions

| Year(s) | Institution/Location | Position/Status | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1858–1864 | Landesschule Pforta (Schulpforta) | Gymnasium student | Intensive classical languages; early philological training |

| 1864–1865 | University of Bonn | Student (theology and classical philology) | Studies under Friedrich Ritschl; shift from theology to philology |

| 1865–1869 | University of Leipzig | Student (classical philology) | Follows Ritschl; reads Schopenhauer; 1867–1868 military service and injury |

| Mar 1869 | University of Leipzig | Honorary doctorate (Philology) | Doctorate awarded on publications, not a dissertation |

| Apr 1869 | University of Basel | Extraordinary Professor of Classical Philology | Appointed at age 24; renounced Prussian citizenship to take post |

| 1870 | University of Basel | Ordinary Professor (tenured) | Promotion with salary increase; strong early teaching reputation |

| 1870–1871 | Franco-Prussian War (service) | Medical orderly (leave from Basel) | Severe illness (dysentery/diphtheria) exacerbates chronic health issues |

| 1879 | Basel and itinerant in Europe | Resignation; independent author | Granted a modest pension; full-time writing in Sils-Maria, Genoa, Nice, Turin |

Use only verifiable dates and roles (Hollingdale, Kaufmann, Cate, letters). Avoid conjecture about motives, do not misdate The Birth of Tragedy (1872) or Human, All Too Human (1878), and do not treat gaps in the record as evidence without sources.

Current Role and Responsibilities (Intellectual Profile)

Nietzsche’s ongoing presence is institutional: a curated corpus, peer-reviewed interpretation, and digital stewardship. These structures define who “speaks for” Nietzsche and how key doctrines are taught and debated today.

Nietzsche scholarship and the Nietzsche archive frame his “current role” as an ongoing object of study, influence, and curation rather than a living author. Stewardship today is distributed across institutions: the Nietzsche-Archiv in Weimar within Klassik Stiftung Weimar; de Gruyter’s Colli–Montinari Kritische Gesamtausgabe/Kritische Studienausgabe (with Gallimard and Adelphi counterparts); and digital platforms such as Nietzsche Source and its eKGWB, which provide open, manuscript-based texts. Editorial boards of Nietzsche-Studien (de Gruyter) and the Journal of Nietzsche Studies (Penn State University Press, for the Friedrich Nietzsche Society) set peer-review agendas, publishing roughly 15–25 essays and 20–30 pieces per year. Large commentary projects like the Heidelberg Academy’s Nietzsche-Kommentar (directed from Freiburg) and university centers and societies convene conferences and shape translations and curricula.

Describing Nietzsche as “currently responsible” means that institutions and scholars assume author-adjacent tasks: canon formation, curricular inclusion, critical editing, translation standards, and digital edition stewardship. The Colli–Montinari standard, which reorders the Nachlass and privileges published works, reorients interpretation: the Übermensch is read as a literary-philosophical figure within Zarathustra’s rhetoric; eternal recurrence is treated cautiously as to doctrinal status, given divergences between notebooks and publications; nihilism is analyzed historically as a diagnosis of European culture, not a system. Modern anthologies—the Cambridge Companion to Nietzsche, the Oxford Handbook of Nietzsche, and series of critical guides—consolidate these norms for teaching, making clear that what “speaks for” Nietzsche is the consensual, philologically controlled text and its vetted commentary.

- “Nietzsche scholarship is stewarded by …”

- “The Nietzsche archive curates and authorizes access to …”

- “Editorial boards serve as public interlocutors for …”

- “Digital repositories maintain the canonical text base for …”

Do not anthropomorphize Nietzsche’s voice or claim new doctrines without citing the Colli–Montinari apparatus and recent peer-reviewed consensus; notebook fragments are not coequal with published works.

Key Achievements and Impact

Analytical overview of Nietzsche’s key works, conceptual achievements, and measurable cross-disciplinary influence with empirical indicators.

Chronological list of Nietzsche key works and impact

| Year | Work | Core concepts | Brief description | Google Scholar citations (approx.) | Noted influence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1872 | The Birth of Tragedy | Apollonian/Dionysian; tragedy | Aesthetic-philosophical analysis of Greek tragedy and culture | 7k+ | Classics, musicology, modernist aesthetics |

| 1878 | Human, All Too Human | Aphorism; naturalism; critique of metaphysics | Transition to experimental style and naturalistic explanations of morality | 4k+ | History of ideas, literary modernism |

| 1883–85 | Thus Spoke Zarathustra | Übermensch; eternal recurrence; nihilism; self-overcoming | Prophetic-poetic work articulating value-creation and life-affirmation | 18k+ | Existentialism, modernist literature; Jung’s psychology |

| 1886 | Beyond Good and Evil | Perspectivism; critique of moral universalism; will to power | Systematic expansion of earlier critiques and epistemic pluralism | 16k+ | Phenomenology, post-structuralism; Heidegger’s lectures |

| 1887 | On the Genealogy of Morality | Genealogy; ressentiment; master/slave morality | Historical method for explaining moral values and guilt | 20k+ | Foucault’s genealogy; critical social theory |

| 1888 | Twilight of the Idols | Revaluation; cultural critique | Late synthesis and polemic against philosophical idols | 6k+ | Cultural criticism, pedagogy |

Avoid inflated claims of causation. Do not assert that Nietzsche “caused” entire movements without documented acknowledgments. Do not misattribute later ideological appropriations (e.g., National Socialism) to Nietzsche’s own positions; distinguish reception history from authorial intent and textual evidence.

Nietzsche key works: achievements and concepts

Nietzsche’s key works from The Birth of Tragedy (1872) through On the Genealogy of Morality (1887) define his major achievements in style and substance. The Birth of Tragedy advances the Apollonian/Dionysian schema for cultural analysis. Human, All Too Human (1878) marks a turn to experimental aphorism and a naturalistic critique of metaphysics. Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883–85) formulates the Übermensch (an ideal of self-transcending value-creation), eternal recurrence (a thought-experiment testing radical affirmation), and nihilism (a diagnosis of collapsing moral foundations). Beyond Good and Evil (1886) develops perspectivism and a systematic critique of moral universalism. Genealogy (1887) reframes moral philosophy by historicizing values through master/slave morality and ressentiment, inaugurating genealogy as a method.

Nietzsche influence: empirical reception and cross-disciplinary impact

Reception is empirically visible: Google Scholar records 20k+ citations for Genealogy, 16k+ for Beyond Good and Evil, and 18k+ for Thus Spoke Zarathustra (accessed 2024). Landmark engagements include Heidegger’s multi-year Nietzsche lectures, Foucault’s essay Nietzsche, Genealogy, History (1971), and Deleuze’s Nietzsche and Philosophy (1962). Movements shaped by these ideas include existentialism, phenomenology, and post-structuralism; in literature, high modernism and expressionism.

Model paragraph linking work to measurable influence: On the Genealogy of Morality (1887) directly informs Michel Foucault’s genealogical method; he cites Nietzsche as method-source, and Nietzsche, Genealogy, History shows 8k+ citations. The effect is traceable in Discipline and Punish and The History of Sexuality, where critique of punitive moral regimes echoes Nietzsche’s account of guilt and punishment. Psychology case study: Carl Jung’s multi-year Zarathustra Seminar (1934–39) integrates self-overcoming into analytical psychology; the published seminar volumes register 3k+ citations and remain widely taught.

Leadership Philosophy and Style (Intellectual Leadership)

Nietzsche led by style as much as by thesis. His aphorisms, parables, and polemics model a form of intellectual leadership that provokes, teaches, and reorganizes debate.

Treating Nietzsche’s philosophical persona as intellectual leadership clarifies how Nietzsche style and Nietzsche rhetorical methods shaped agendas rather than merely opinions. He leads by form: aphorism (density, ambiguity), metaphor (hammer, abyss), and persona (Zarathustra) create a staged arena where readers must perform interpretation. This pedagogical dramaturgy is iconoclastic—he breaks inherited categories—yet it is also formative, training readers to withstand risk, irony, and conceptual revaluation. The polemical register (e.g., against Christian-moral and metaphysical habits) functions less as dogma than as strategic shock, clearing space for experimental thinking. Across texts and letters, Nietzsche curates distance, provocation, and exemplarity to redirect debates toward value-creation, genealogy, and style as method.

Exemplar aphorism: “Whoever fights monsters… the abyss gazes back” (BGE 146). Rhetorically, it compresses causal caution, mirroring, and reflexivity into a memorable image; philosophically, it warns that negation can reproduce what it opposes. As leadership, the sentence sets norms for self-scrutiny in conflict, instructing readers how to contest without becoming the thing contested. The broader method—fragmentation, persona, and polemic—advances his aim to replace system-building with problem-posing and character formation. Implications for contemporary thought leadership (in scholarship and tech): lead with problem-frames not blueprints; use crafted personae, narratives, and minimal theses to catalyze inquiry; pair sharp slogans with processes for context and iteration, resisting premature doctrinal closure.

- Leadership style: provocative, iconoclastic, pedagogical; authority via form, not office.

- Stylistic leverage: aphorism for memorability, parable for enactment, polemic for clearance.

- Applications: frame-first strategy, persona-driven communication, iterative and context-aware critique.

Primary-text snapshots of method

| Mode | Passage (short) | Work/Section | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aphorism | “Whoever fights monsters… the abyss gazes back.” | Beyond Good and Evil 146 | Reflexive caution; memorability |

| Parable | “I tell you of three metamorphoses: camel, lion, child.” | Zarathustra, Of the Three Metamorphoses | Dramatizes self-overcoming |

| Polemic | “I call Christianity the one great curse…” | The Antichrist 62 | Value-inversion; shock to norms |

Public interactions and contemporaneous responses

| Interaction | Date | Counterparty | Outcome/Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attack on The Birth of Tragedy (Zukunftsphilologie!) | 1872 | Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff | Public controversy; Erwin Rohde’s defense |

| Lectures on Nietzsche (Aristocratic Radicalism) | 1888 | Georg Brandes | International reception; correspondence of thanks |

| Break with Wagner; later critique in The Case of Wagner | 1876–1888 | Richard Wagner | Polarized reviews; repositioned Nietzsche’s audience |

Do not equate Zarathustra or other literary personae with settled doctrine, nor treat aphorisms as context-free, systematic propositions.

Industry Expertise and Thought Leadership

Nietzsche ethics AI meets knowledge provenance and automation: this section translates Nietzsche thought leadership into actionable methods for AI governance, knowledge modeling, and research operations, with pragmatic transfers, limits, and research questions.

Nietzsche’s toolkit—philology, aesthetics, moral psychology, genealogy—maps to industry problems in research, KM, and automation. Philology becomes knowledge modeling: rigorous versioning, semantic disambiguation, and traceable citation in ontologies and catalogs. Aesthetics informs evaluation of generative systems via style, taste, and norm-sensitivity metrics. Moral psychology guides stakeholder analysis and incentive design. Genealogy becomes governance: provenance-first workflows, value-drift audits, and policy lineage for models and datasets. This is actionable Nietzsche thought leadership for technical teams.

Concrete transfers: genealogical audits can be implemented with W3C PROV-O, OpenLineage, Apache Atlas, Model Cards, and Datasheets for Datasets, making origins and value assumptions inspectable. In algorithmic governance, Nietzschean critique exposes hidden hierarchies behind fairness KPIs, echoing sociotechnical work on abstraction in AI. Cross-disciplinary applications show how ressentiment frames resistance to automated authority, while will to power reframes capability building as creative agency, improving change management and AI adoption.

Use-case: eternal recurrence as iterative validation. Treat each pipeline run as a recurrence test: if you had to live with this exact output forever, would you still ship? Operationalize via CI/CD gates that replay datasets, prompts, and policies across time, checking stability, error budgets, and ethical constraints. Recurrence deltas quantify value drift and regressions, informing rollback or retraining in automated workflows.

Limits: Nietzsche is diagnostic, not prescriptive; genealogy questions inputs but does not set thresholds. Anti-foundationalism risks relativism if unmoored from standards. Mitigate with multi-stakeholder governance, domain regulation, and reproducible audits. For Sparkco, the pay-off is methodological: embed genealogical tracing beside metrics, and pair moral-psychology insights with adoption KPIs to anticipate resistance without pathologizing users. Guard against rhetorical appropriation that excuses harmful optimization.

- Design a PROV-compliant genealogical audit that links objectives, value statements, labeling policies, and model artifacts; evaluate with Apache Atlas or OpenLineage.

- Operationalize ressentiment ethically: develop telemetry that detects perceived loss of agency during rollout without stigmatizing users; correlate with adoption KPIs.

- Define metrics for will to power as capability growth (autonomy, creativity) rather than dominance; instrument in product analytics and LLM evals.

- Quantify value drift across fine-tunes and releases via recurrence deltas; specify governance thresholds that trigger review, rollback, or retraining.

Cross-disciplinary operationalizations and tools

| Framework or article | Domain | Operationalization |

|---|---|---|

| Datasheets for Datasets (Gebru et al.) | Data governance | Genealogical documentation of dataset origins, intentions, and power-laden decisions |

| Model Cards for Model Reporting (Mitchell et al.) | Model transparency | Surfacing provenance and normative assumptions for inspection |

| W3C PROV-O + OpenLineage + Apache Atlas | Knowledge provenance | End-to-end lineage captures the moral ancestry of outputs |

| Fairness and abstraction in sociotechnical systems (Selbst et al., 2019) | Algorithmic governance | Critique of problem formulations aligns with genealogical unmasking of value hierarchies |

Do not use Nietzschean rhetoric to justify unethical optimization or exclusionary ideologies; anchor Nietzsche ethics AI work in standards, stakeholder review, and auditability.

Board Positions and Affiliations (Academic Networks)

Nietzsche held no corporate board roles. This section documents Nietzsche affiliations in universities, mentorships, Nietzsche correspondences, editorial relationships, and modern custodians that functioned as intellectual networks shaping his career and legacy.

Nietzsche did not serve on corporate boards; his influence moved through formal academic posts, mentorships, correspondence networks, and publishing/editorial ties. Writers should emphasize verifiable institutional affiliations (Bonn, Leipzig, Basel), documented exchanges with key interlocutors, and the later institutions that steward and contest his legacy.

Personal networks were decisive for appointments, reception, and circulation of texts: Ritschl’s patronage enabled the Basel chair; Wagner’s circle amplified early visibility; friendships with Overbeck and Burckhardt sustained his Basel years; and collaborations with Peter Gast shaped manuscripts and proofs. Modern custodians—especially the Nietzsche-Archiv in Weimar and the Colli–Montinari critical editions—now effectively “govern” access and interpretation through archival control and editorial standards.

Formal Institutional Affiliations

| Institution | Role/Position | Dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schulpforta (Pforta) | Student | 1858–1864 | Humanist gymnasium training |

| University of Bonn | Student (theology, then philology) | 1864–1865 | Transferred to Leipzig |

| University of Leipzig | Student (classical philology) | 1865–1868 | Mentored by F. W. Ritschl |

| University of Leipzig | Doctor of Philosophy (honorary, without dissertation) | 1869 | Conferred on Ritschl’s recommendation |

| University of Basel | Professor of Classical Philology | 1869–1879 | Resigned due to ill health; maintained ties with Basel colleagues |

Editorial and Legacy Custodians

| Institution/Person | Function | Dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ernst Schmeitzner (publisher) | Publisher of early works | c. 1876–1886 | Relationship ended; Nietzsche republished later works independently |

| C. G. Naumann (printer/publisher) | Printing and reissues | from 1886 | Enabled author-controlled editions |

| Peter Gast (Heinrich Köselitz) | Editorial aide, copyist, proofreader | c. 1876–1889 | Close collaborator on manuscripts and corrections |

| Nietzsche-Archiv (Weimar) | Posthumous custodian | from 1894 | Led by Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche; controversies over editing and politicization |

| Colli–Montinari critical editions | Scholarly critical text | from 1967 | Basis for modern editions (e.g., de Gruyter); corrects earlier Archive distortions |

| Klassik Stiftung Weimar | Institutional steward of Archive holdings | present | Administers access and conservation |

Do not invent modern corporate board roles or attribute organizational agency that did not exist in Nietzsche’s era; document only verifiable affiliations and editorial custodianship.

Key Correspondents and Intellectual Networks

Documented Nietzsche correspondences that shaped alliances and reception include the following (date ranges approximate and publication-backed):

- Richard Wagner: intensive exchange c. 1869–1878; alliance then rupture

- Paul Rée: close intellectual collaboration c. 1878–1882

- Lou Andreas-Salomé: concentrated correspondence in 1882

- Franz Overbeck: sustained support and letters c. 1869–1889

- Jakob Burckhardt: collegial exchanges during Basel years (1870s–1880s)

- F. W. Ritschl and Erwin Rohde: mentorship and peer network from the 1860s onward

Template for Presenting Affiliations

Use concise bullets with dates; include role and sourceable notes; avoid implying corporate governance.

- [Year–Year] — Institution: Role/Position — brief note (mentor, department, publication link).

- [Year] — Publisher/Editor: Function — scope of collaboration (e.g., proofs, reissue).

- [Year–] — Archive/Foundation: Custodianship role — access or edition governance.

Education and Credentials

Concise overview of Nietzsche education and Nietzsche credentials: institutions, dates, mentors, and early publications that culminated in his Basel professorship. Verified highlights emphasize formal training without inflating degree status.

Nietzsche’s philological training—textual criticism, historical-linguistic method, and rigorous source scrutiny—directly informed his later philosophical practice, from genealogical arguments to close readings that dismantle inherited moral and religious claims. These credentials and networks, especially Ritschl’s sponsorship, enabled the Basel appointment and shaped The Birth of Tragedy and subsequent critiques; the honorary doctorate should not be treated as a modern PhD equivalent.

- 1858–1864 — Landesschule Pforta (Schulpforta): intensive classical education; completed Abitur in 1864.

- September 1864–March 1865 — University of Bonn: matriculated in theology and classical philology; abandoned theology after one semester; studied with Friedrich Wilhelm Ritschl.

- 1865–1869 — University of Leipzig: classical philology under Ritschl; close peer Erwin Rohde; early philological essays published 1867–1869 (e.g., in Rheinisches Museum für Philologie) on Greek authors such as Diogenes Laertius and Theognis.

- March 1869 — University of Leipzig: awarded an honorary doctorate; no dissertation or habilitation submitted.

- April 1869 — University of Basel: appointed Professor of Classical Philology at age 24, on Ritschl’s strong recommendation; service continued until resignation due to illness in 1879.

Do not overstate Nietzsche credentials: he held no completed doctorate or habilitation before Basel; the 1869 Leipzig degree was honorary. Avoid inventing modern equivalences, and prefer primary documentation (matriculation records, Ritschl’s letters, Basel appointment files) over tertiary summaries.

Publications, Lectures, and Public Speaking

A concise guide to Nietzsche publications, his Basel lectures, and modes of public engagement, with dates aligned to Colli–Montinari (KGW/KSA).

For researchers tracking Nietzsche publications, the Colli–Montinari KGW/KSA furnish reliable first-edition dates, variants, and editorial controls. Thus Spoke Zarathustra publication date: 1883–1885 in four parts; second editions and revised printings are recorded in KSA. The list below selects primary works with brief theses; dates indicate first publication unless otherwise stated.

Key statistics on publications and public engagements

| Metric | Value | Date/Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basel professorship | 10 years | 1869–1879 | Chair in Classical Philology; resigned for health |

| Public lecture series On the Future of Our Educational Institutions | 5 lectures | 1872 | Delivered to a general Basel audience |

| Inaugural lecture Homer and Classical Philology | 1 lecture | 1869 | University public lecture |

| Major books first issued (lifetime) | 9 | 1872–1889 | Excludes posthumous first editions |

| Posthumous first editions | 3 | 1895–1908 | The Antichrist (1895), Nietzsche contra Wagner (1895), Ecce Homo (1908) |

| KSA volumes (Colli–Montinari) | 15 | 1980– | Kritische Studienausgabe |

| KGW planned volumes | ~50 | 1964– | Kritische Gesamtausgabe scope |

| Surviving letters (approx.) | over 1,000 | 1850s–1889 | Edited in Colli–Montinari Briefe |

Do not conflate posthumous editions with original texts: the Will to Power was a constructed compilation in early 20th-century editions; Colli–Montinari disassembled it, restoring fragments to their chronological notebooks and noting redactions.

Authoritative citations: Colli–Montinari KGW (since 1964) and KSA (15 vols., since 1980); the digital eKGWB incorporates thousands of corrections and variant readings.

Annotated primary works (selection)

- The Birth of Tragedy (1872): Philology fused with aesthetics, opposing Apollonian form to Dionysian ecstasy.

- Untimely Meditations (1873–1876): Four polemics critiquing modern culture, history, and German Bildung.

- Human, All Too Human (1878–1880): Aphoristic naturalism shifting from metaphysics to scientific psychology.

- Daybreak (1881): Moral critique as affect-psychology, probing conscience, pity, and ressentiment.

- The Gay Science (1882; rev. 1887): Gay knowing, style, and the announcement of the death of God.

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883–1885): Exemplary entry—poetic manifesto of the overhuman and eternal recurrence.

- Beyond Good and Evil (1886): Systematic critique of dogmatic philosophy and herd morality.

- On the Genealogy of Morals (1887): Historical polemic tracing priestly values and the ascetic ideal.

- Twilight of the Idols (1889): Late summa; compressed “hammer” critique of cultural and philosophical idols.

- The Antichrist (written 1888; pub. 1895): Posthumous attack on Christian morality’s origins and authority.

Lectures and public engagement

At Basel (1869–1879) he taught courses on the Pre-Platonic philosophers (1872), Greek rhetoric and literary history, and delivered public interventions: the inaugural Homer and Classical Philology (1869) and the five-lecture series On the Future of Our Educational Institutions (1872). His lecture style combined dense philological handouts with extemporaneous provocation; documentation survives in KGW and Basel archives. Beyond the classroom, he reached audiences through books and select philological papers (e.g., Rheinisches Museum für Philologie), publisher prospectuses, and an extensive correspondence that doubled as a public medium. Reviews amplified visibility, especially around The Case of Wagner (1888), though he seldom replied in print.

Awards, Recognition, and Posthumous Reputation

Nietzsche’s lifetime honors were modest, but posthumous curation, politicized appropriations, and critical scholarship transformed his visibility. Debates over the Nietzsche-Archiv and subsequent textual restorations continue to shape Nietzsche reception and Nietzsche reputation.

During his lifetime, Nietzsche received few formal honors beyond his extraordinary 1869 appointment as Professor of Classical Philology at Basel (accompanied by a Leipzig doctorate awarded without dissertation). He resigned in 1879 for health reasons and never accrued the prizes or academy memberships typical of peers. Posthumously, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche founded the Nietzsche-Archiv in Weimar in 1894, centralizing manuscripts but provoking enduring controversy over editorial interventions, especially the compilation The Will to Power (1901/1906). These practices shaped early Nietzsche reception and facilitated later political appropriations. In the 1930s–40s, Nazi ideologues selectively mined slogans and themes—most notoriously a racialized Übermensch—while the Archiv courted regime attention; Hitler’s 1934 visit amplified the image. After 1945, scholarly rebuttals shifted Nietzsche reputation: in the Anglophone world, Walter Kaufmann’s 1950 study challenged the Nazi reading; from 1967, the Colli–Montinari critical editions (KGW/KSA) reconstructed a reliable corpus from notebooks, undermining spurious posthumous texts. Late-20th-century reevaluations by Deleuze, Foucault, and analytic interpreters consolidated more nuanced views. Institutional recognition followed: specialist societies, journals, curated archives within the Klassik Stiftung Weimar, and recurring public festivals and conferences. This evolving reception reframed key concepts: the Übermensch as ethical-existential self-overcoming rather than racial doctrine; eternal recurrence as a thought experiment testing affirmation, not cosmology; and nihilism as a diagnosis that prompts revaluation rather than an endorsement.

Timeline of Nietzsche’s Reputation Shifts and Recognitions

| Year/Period | Event/Recognition | Impact on Reception | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1869 | Basel professorship; Leipzig doctorate in absentia | Rare early-career academic honor | Resigns 1879 due to health |

| 1894 | Nietzsche-Archiv founded in Weimar by Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche | Centralizes legacy; establishes editorial gatekeeping | Source of later authenticity controversies |

| 1901/1906 | Posthumous compilations of The Will to Power | Widely read but textually problematic | Rearranged notes shaped early interpretations |

| 1933–1945 | Nazi-era appropriation; Hitler’s 1934 visit to the Archiv | Politicized, racialized image spreads | Selective readings by ideologues (e.g., Baeumler) |

| 1950 | Walter Kaufmann’s rehabilitation in Anglophone scholarship | Challenges Nazi reading; renews philosophical interest | Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist |

| 1967–1988 | Colli–Montinari critical editions (KGW/KSA) | Restores textual integrity; debunks spurious composites | Basis for modern scholarship |

| 1990s–present | Societies, journals, and museum-led events; Archiv within Klassik Stiftung Weimar | Institutional consolidation and global teaching | Broader, plural scholarly approaches |

Avoid sensational claims of rediscovery and simplistic links between Nietzsche and specific political movements without primary-text and editorial evidence; reputational narratives must be grounded in critical editions and historical context.

Model paragraph

Nietzsche’s legacy has earned institutional stature through archives, critical editions, and international scholarship, yet responsible interpretation demands philological care: assess editorial histories, resist political co-option, and weigh concepts like Übermensch, eternal recurrence, and nihilism within their textual and historical contexts.

Personal Interests, Life, and Community

Drawing on Nietzsche correspondence, this section outlines Nietzsche personal life: documented interests in music, philology, and hiking; selective social circles; health-driven work rhythms; and post-1889 care by family and friends.

Nietzsche personal life emerges clearly in Nietzsche correspondence, which records passions for philology, classical music, and mountain walks. He played piano, composed small pieces, and early on wrote admiring letters to Richard Wagner before an intellectual breach in the later 1870s. His social world was selective but rich: Erwin Rohde, Franz Overbeck, Jacob Burckhardt, Peter Gast, and in 1882 the circle of Lou Andreas-Salomé and Paul Rée. Example snippet: "an idyllic little nest among beautiful woods" (to Lou Andreas-Salomé, July 1882; cite via critical editions such as KGB).

He favored a solitary, itinerant routine; after resigning in 1879, chronic migraines, eye strain, and digestive illness set the cadence of travel and work. He sought high-altitude summers in the Upper Engadine (notably Sils-Maria) and mild winters along the Riviera or in Italy; letters link clear air, long hikes, and piano practice to productive bursts, followed by enforced rest during attacks. This pattern appears in notes to friends arranging lodging, manuscripts, and convalescence.

In January 1889 he collapsed in Turin. Friends, especially Overbeck, secured clinical care (Basel, then Jena), after which his mother Franziska cared for him in Naumburg; from 1897 his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche oversaw his Weimar household. Formal charitable or civic engagements are scarcely attested; beyond collegial aid and small favors, he lived apart from associations. The broader academic and literary milieu nonetheless preserved his papers and enabled posthumous editions—facts essential to sober treatments of Nietzsche personal life.

Citation guidance: quote short, verifiable phrases with recipient, place, and date (e.g., Letter to Lou Andreas-Salomé, July 1882) and reference critical editions of the Nietzsche correspondence (KGB/KGW) or reliable scholarly biographies.

Avoid sensational claims about intimate motives or medical diagnoses; do not include private details unsupported by sources, and do not romanticize anecdotes in ways that eclipse the documented record.

Practical Applications: From Philosophical Analysis to Systematic Thinking

Nietzsche practical applications for Sparkco: translate genealogy into a provenance-first knowledge management genealogy model; apply eternal recurrence to iterative validation and scenario testing; and treat nihilism as explicit value-assessment workflows. Deliverables: concrete steps, KPIs, and pilots integrated with data governance and automation.

Concept-to-method mappings for Sparkco

Operationalize Nietzsche’s genealogy as a provenance discipline: track not only data transforms but the historical motives, incentives, and authorities shaping each choice. Eternal recurrence informs rigorous reruns of scenarios to test durability across time and change. Confronting nihilism becomes explicit value modeling: make objectives, harms, and trade-offs auditable. This translation supports knowledge management genealogy by combining machine-captured lineage with human-authored rationales, linking concept, context, and control. Tooling aligns with existing stacks (W3C PROV, OpenLineage/Apache Atlas, Great Expectations, Monte Carlo/backtesting suites) while preserving auditability and stakeholder comprehension.

- Genealogy → Provenance model: inventory critical datasets/models and decision points.

- Model sources, agents, and activities using W3C PROV/PROV-O.

- Automate lineage via OpenLineage/Apache Atlas; add narrative decision logs in version control.

- Output: queryable provenance graph plus human-readable decision history.

- Eternal recurrence → Iterative validation: define canonical scenarios and edge cases.

- Build automated harness with Monte Carlo/backtesting and chaos tests.

- Schedule recurrence on each code/data change; compare to baselines and SLAs.

- Gate releases on scenario pass rates and drift alarms.

- Confronting nihilism → Value assessment workflows: elicit values, disvalues, and constraints with stakeholders.

- Translate into measurable objectives/harms with weights and thresholds.

- Implement value checks in pipelines and review boards (pre-merge, pre-release).

- Log rationales; publish value-impact notes alongside model cards.

- Concept → Hypothesis → Implementation → Evaluation.

- Example: Genealogy of feature selection bias in churn model.

- Hypothesis: lineage + rationales will cut interpretive errors by 30%.

- Implement PROV + Atlas + decision logs + expectations; evaluate error rate, audit time, confidence delta.

Concept → Method → Tool mapping

| Concept | Operational method | Tools/Standards | Pilot objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genealogy | Lineage-of-decisions and influences | W3C PROV/PROV-O; OpenLineage; Apache Atlas; Git decision logs | Raise provenance completeness and audit speed |

| Eternal recurrence | Recurring scenario/backtest loops | Great Expectations; Monte Carlo/backtesting; Chaos tooling | Stabilize performance across changes |

| Nihilism | Explicit value modeling and checks | Objective-weight matrices; review boards; model cards | Align outputs with declared values |

Pilot experiments and KPIs

Run three 4-week pilots: (1) genealogical review for two high-impact datasets; (2) scenario-recurrence harness for a forecasting service; (3) value-assessment gates for a prioritization model. Track baseline vs post-pilot metrics and document remediation costs to size ROI and operational load.

KPIs for philosophical integration

| Metric | Definition | Target |

|---|---|---|

| Provenance completeness % | Pipeline steps with PROV entities documented | ≥95% |

| Interpretive error reduction % | Drop in stakeholder misreadings in explainability tests | ≥30% in 2 quarters |

| Scenario validation coverage % | Critical scenarios automated and recurring | ≥90% |

| Time-to-root-cause (hours) | Mean hours to trace an incident to origin | -40% |

| Stakeholder confidence delta | Pre/post survey score change | +1.0 on 5-point scale |

Research directions

Interdisciplinary anchors: W3C PROV-DM and PROV-O (Moreau, Missier et al.) operationalize provenance; Buneman, Khanna, Tan on data provenance; Simmhan, Plale, Gannon survey provenance techniques; Bowker and Star’s Sorting Things Out and Edwards et al.’s Knowledge Infrastructures link historical-genealogical analysis to metadata and organizational design. Museum/CIDOC CRM and digital humanities metadata practices exemplify genealogical analysis applied to provenance strategies.

Risks and ethical limits

Limits: over-documentation can slow delivery; recurrence loops risk overfitting to known scenarios; value models can encode sponsor bias; deeper lineage may expose sensitive actors or privacy risks. Governance must enforce explainability, consented data use, and redress. Treat Nietzschean frames as probes, not as optimization dogma.

Do not use Nietzschean rhetoric to justify opaque optimization or value-free automation. Require transparent criteria, auditable decisions, and accountable owners for every automated step.

Critical Reception and Debates

A concise survey of Nietzsche criticism charting major schools, core controversies, and their implications for ethics and knowledge work.

Nietzsche criticism has unfolded in waves. Early reception oscillated between scandal and nationalist misuse, culminating in politicized readings before World War II. Postwar rehabilitation by Walter Kaufmann (1950) and R. J. Hollingdale (1965) reframed Nietzsche as a rigorous, non-totalitarian thinker, while existentialists emphasized agency, anxiety, and the Übermensch as a task rather than a type. Parallel analytic engagements (A. C. Danto 1965) and later naturalistic reconstructions (Brian Leiter 2002) queried the coherence of will to power, nihilism, and value creation, often stressing argumentative clarity and textual evidence over grand system-building.

Interpretive schools diverge around eternal recurrence, Übermensch interpretations, and nihilism. Heidegger’s 1936–46 lectures (published 1950–66) cast Nietzsche as “the last metaphysician of the West,” taking recurrence as the ontological ‘eternal return of the same’ grounded in will to power. Deleuze (1962) recasts recurrence as selective affirmation and difference; Foucault (1971) mobilizes genealogy for power analysis. Disputes persist over Zarathustra’s status (parable vs doctrine), Nietzsche and politics, and cosmological vs ethical readings. These debates shape ethics and knowledge work through decision-heuristics and genealogical audits of concepts and institutions.

Balanced contrast on recurrence: ethical readers cite The Gay Science 341 and Zarathustra to treat it as a thought experiment testing life-affirmation; ontological readers, following Heidegger, turn to the notebooks and links to will to power to argue metaphysical necessity. Both appeal to different textual strata (published aphorisms vs Nachlass) and face challenges: ethical views must answer cosmological hints; ontological views must justify privileging late notes. Arguments should be source-based, non-polemical, and contextualize fringe positions.

Comparison of major interpretive schools and controversies

| School/Trend | Key figures | Core theses | Primary evidence | Key controversies | Influential works (year) | Contemporary implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early rehabilitation (postwar) | Walter Kaufmann; R. J. Hollingdale | Reframes Nietzsche as rigorous, anti-totalitarian; emphasizes ethical-existential renewal | Published texts; editorial history; biographical correction | Politics; Nazi appropriation; translation choices | Kaufmann 1950; Hollingdale 1965/1968 | Reopened university study; informed ethics curricula |

| Existentialist appropriations | Karl Jaspers; Albert Camus | Focus on authenticity, agency, self-overcoming; Übermensch as task | The Gay Science; Zarathustra; autobiographical passages | Over-personalization; downplaying metaphysics | Jaspers 1936; Camus 1951 | Therapeutic ethics; decision-making under absurdity |

| Heideggerian ontology | Martin Heidegger | Nietzsche as “last metaphysician”; recurrence as ontological ‘return of the same’ | Nachlass; will to power; systematic reconstruction | Cosmological vs ethical status; priority of notes | Heidegger 1950–66, Nietzsche | History of metaphysics; ontology in continental philosophy |

| Post-structuralist readings | Gilles Deleuze; Michel Foucault | Recurrence as selective affirmation/difference; genealogy of power/knowledge | Close readings; On the Genealogy of Morality; Zarathustra | Politics of hierarchy; anti-humanism; method | Deleuze 1962; Foucault 1971 | Critical theory; audits in knowledge work and institutions |

| Analytic-naturalist critiques | A. C. Danto; Alexander Nehamas; Brian Leiter | Conceptual analysis; aestheticism (life as literature); naturalized morality | Argument reconstruction; GS; Genealogy | Normativity; truth; unity of doctrine | Danto 1965; Nehamas 1985; Leiter 2002 | Moral psychology; metaethics; philosophy of science |

| Political contests | Domenico Losurdo; Keith Ansell-Pearson | Aristocratic radicalism vs liberal/left appropriations | Aphorisms on rank, breeding, ressentiment; historical context | Is Nietzsche political, anti-political, or elitist? | Losurdo 2002; Ansell-Pearson 1994 | Cautions for political theory and reception |

| Status of Zarathustra | Karl Löwith; Laurence Lampert | Doctrinal centerpiece vs poetic-literary parable | Narrative form; prologue and speeches; cross-references | How literal are its ‘teachings’? | Löwith 1935; Lampert 1986 | Hermeneutics; pedagogy; canon formation |

Avoid polemical positions without source evidence; identify quotations, dates, and editions, and do not favor fringe readings without indicating their minority status in scholarship.

Ethical Considerations and Critiques

Applying Nietzschean concepts today requires heightened caution due to documented distortions and high stakes in research and automation. This section outlines key misuses, scholarly corrections, and practical guardrails for ethically informed adaptation.

Ethical scrutiny is essential because Nietzsche’s lexicon has a long record of politicized distortion. The Nazi apparatus—via Alfred Rosenberg and Alfred Baeumler, and abetted by Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche’s tendentious editing of The Will to Power—propagated a racialized Übermensch and a crude will to power. Scholarly corrections emphasize that Nietzsche denounced anti-Semitism, nationalism, and state idolatry; see Walter Kaufmann’s analyses and the Colli–Montinari critical edition, alongside contemporary work by Brian Leiter, which documents the incompatibility of fascist readings. Responsible engagement must therefore foreground provenance, translation choices, and context to preempt Nietzsche misuse and to uphold rigorous Nietzsche ethics.

In contemporary research and automation, adapt Nietzschean insights cautiously: treat the Übermensch as a metaphor for self-overcoming, not a warrant for hierarchy; distinguish descriptive nihilism from ethical endorsement; and map concepts to domain-neutral principles. Recommended anchors include transparency, context-sensitivity, non-maleficence, pluralistic oversight, and contestability. Teams should publish interpretive rationales, cite passages, and include counter-interpretations. Explicit red flags include decontextualization, value absolutism, and any instrumentalization to justify harm. Above all, ethically responsible translation and framing must acknowledge the complexity and tensions in Nietzsche’s corpus; simplification erases meaning and risks repetition of past abuses.

- Cite source texts and explain translation choices (e.g., Colli–Montinari; Kaufmann), with line references.

- Document how concepts are operationalized and which readings are excluded, with justification.

- Run harm and misuse analyses, including red teaming for supremacist or deterministic interpretations.

- Provide transparency artifacts (model cards, decision logs) and enable contestation and appeal.

- Mandate human oversight and an opt-out when philosophical guidance is uncertain or high-risk.

- Decontextualization of aphorisms or slogans detached from surrounding passages.

- Value absolutism presented as Nietzschean despite his anti-dogmatic stance.

- Appeals to Übermensch to rank persons or groups in policy or product decisions.

- Any system change justified by vague will to power rhetoric without textual grounding.

Important ethical guardrails and recommendations

| Guardrail/Recommendation | Why it matters | Red flags to watch | Concrete actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Responsible translation and provenance | Prevents semantic drift from tendentious editions | Slogans without citations; reliance on The Will to Power notebooks as doctrine | Use critical editions; document translator choices; cite passages |

| Context-sensitivity and interpretive framing | Nietzsche writes aphoristically; context shifts meaning | Decontextualization; cherry-picking lines | Provide surrounding text summaries; include competing readings |

| Anti-harm and non-instrumentalization | Philosophy must not license exclusion or violence | Claims of superiority, eugenics, or policy-by-Übermensch | Ethics review; reject applications that increase harm |

| Transparency and auditability | Enables scrutiny and correction | Opaque inspiration pipelines | Publish model cards, decision logs, and data lineage |

| Pluralistic oversight and contestability | Counters value absolutism | Single-author final say; no dissent recorded | Include diverse experts; require dissent logs and appeal paths |

| Historical awareness of Nietzsche misuse | Prevents repetition of propaganda-era errors | Silence about Nazi appropriation | Include historical disclaimers; training on scholarly rebuttals |

Do not instrumentalize Nietzsche to justify harm or to erase the complexity of his thought; treat all adaptations as provisional, documented hypotheses subject to expert review.